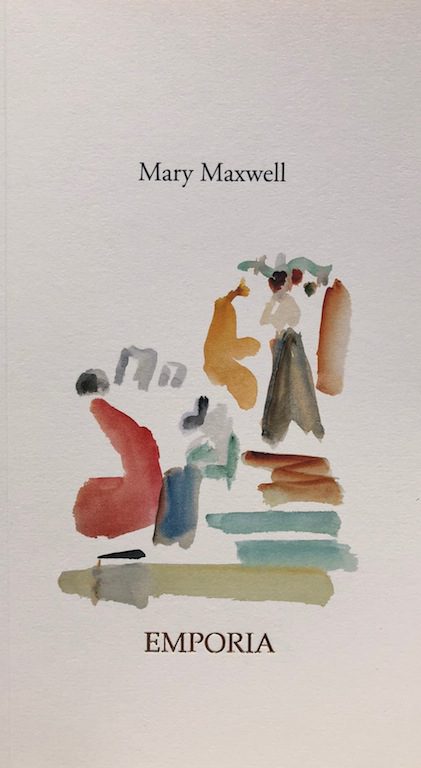

In Mary’s Maxwell’s second collection, a tripartite set of prose poems superimposes the vanished world of a small-town department store with a New Yorker’s experience of post-9/11 collapse. In a series of engaging tableaux, a young woman experiences early adulthood, marriage and motherhood through the lens of late twentieth-century shopping. The series of paired paragraphs are each joined by the page’s blank space, a meaningful gap: “Your gift with purchase, unexpected, the discovery of form’s sublime arbitrariness. In wordless intervals between ruminations your true subject was found: What’s no longer there.”

As James Dickey wrote of the poet’s distinctive approaches:

How much I admire Mary Maxwell’s talent. The most intelligent and scholarly of the poets I saw in my seven years of judging the [Yale Younger Poets] competition, Maxwell has a very good ear, a discriminating eye, and that most indispensable quality a poet must have, if she really is a poet: an original way of looking at things, a definite stance.

Formally ambitious yet full of modest charms, Emporia’s “divine comedy” concludes with a spunky apology to the legacies of Whitman and O’Hara: “The reader was to conceive of a soul’s lonely climb, period spent in purifying exile, then starlit daredevil escape. Of course it’s all been done before, but now at last you know where this too was heading: The impetus behind these words was love, author of all genuine movement.”